Coronary Blood Flow

The perfusion of the heart itself is a particularly important aspect of physiology to understand.

Both the anatomy and the physiology are relevant to clinical practice, such as by helping localising coronary lesions from ECG changes, to providing guidance on the best intraoperative management of patient with ischaemic heart disease.

Both the anatomy and the physiology are relevant to clinical practice, such as by helping localising coronary lesions from ECG changes, to providing guidance on the best intraoperative management of patient with ischaemic heart disease.

Key Points

- Myocardial oxygen extraction is already high at rest, so increased demand must be met by increased coronary blood flow.

- The high intramural pressures in systole, limit blood flow, so most of myocardial perfusion occurs in diastole.

- Tachycardia reduces the time span for myocardial perfusion (shorter diastole) as well as increasing demand.

- Pressure work requires more oxygen than volume work, which is an important physiological consideration for the supply/demand balance.

- Overall, the best balance of supply versus demand must be achieved.

Anatomy

The blood flow to the heart is provided by the two coronary arteries; the left coronary artery, and the right coronary artery.

Their anatomy is useful to understand the impact of a coronary artery occlusion (i.e. an MI) on the heart itself, as it can demonstrate which parts of the heart will be ischaemic or infarcted.

An understanding of the major branches is also important for the same reason.

Their anatomy is useful to understand the impact of a coronary artery occlusion (i.e. an MI) on the heart itself, as it can demonstrate which parts of the heart will be ischaemic or infarcted.

An understanding of the major branches is also important for the same reason.

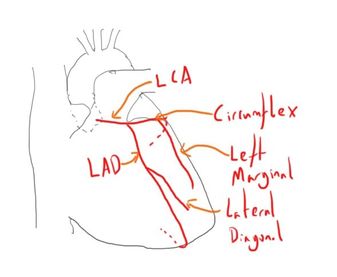

Left Coronary Artery

Arises in the aortic root from behind the left coronary cusp of the aortic valve.

It quickly divides into the two main branches:

The left coronary artery supplies:

It quickly divides into the two main branches:

- The left anterior descending (LAD) artery (also known as posterior interventricular)

- The circumflex artery

- Left marginal artery

- Lateral diagonal branch

The left coronary artery supplies:

- The left atrium

- Most of the left ventricle

- Some of the right ventricle

- Most of the interventricular septum (anterior ⅔) including the AV bundle

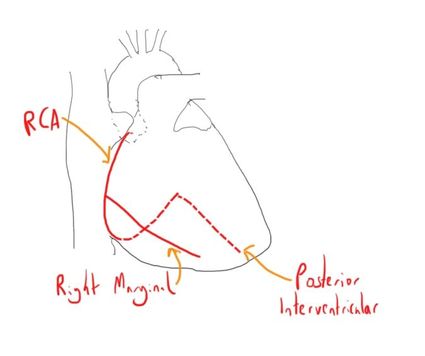

Right Coronary Artery

Arises in the aortic root, behind the right coronary cusp of the aortic valve.

Typically supplies the right atrium and right ventricle

It gives off its main branch, the marginal artery, which primarily supplies the lateral wall of the right atrium and ventricle.

It will commonly continue to provide the posterior descending artery (or posterior interventricular). This determines the ‘dominance’ of the heart (see below) and this artery supplies the posterior wall of both ventricles.

The right coronary artery will generally supply:

Typically supplies the right atrium and right ventricle

It gives off its main branch, the marginal artery, which primarily supplies the lateral wall of the right atrium and ventricle.

It will commonly continue to provide the posterior descending artery (or posterior interventricular). This determines the ‘dominance’ of the heart (see below) and this artery supplies the posterior wall of both ventricles.

The right coronary artery will generally supply:

- The right atrium

- Much of the right ventricle

- Some of the left ventricle (diaphragmatic aspect)

- SA node (in 60% of people)]

- AV node (in 80%)

- Some of the interventricular septum (usually posterior ⅓)

Dominance

The exact anatomy, and therefore the resulting distribution of myocardial perfusion, is not the same in all patients.

One side of the major arteries is said to be ‘dominant’, in that it supplies more of the myocardium.

The distribution of dominance is:

Other variations in coronary anatomy between people also occur.

The exact anatomy, and therefore the resulting distribution of myocardial perfusion, is not the same in all patients.

One side of the major arteries is said to be ‘dominant’, in that it supplies more of the myocardium.

The distribution of dominance is:

- Right sided dominant - 50%

- Left side dominant - 20%

- Joint dominance - 30%

Other variations in coronary anatomy between people also occur.

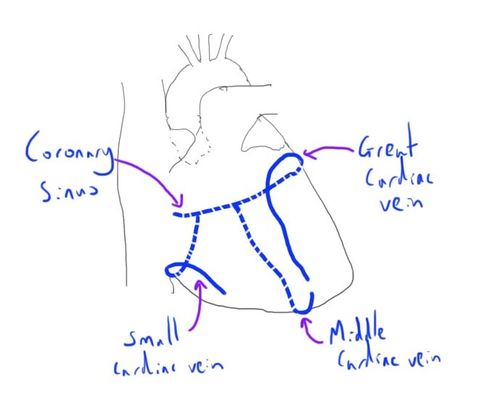

Venous Drainage

The majority of the venous drainage of the heart is through the cardiac veins, and subsequently the coronary sinus, into the right atrium.

These are:

A small volume of venous blood drains directly into other heart chambers via different routes:

These are:

- Great cardiac vein

- Middle cardiac

- Small cardiac vein

A small volume of venous blood drains directly into other heart chambers via different routes:

- Thebesian veins

- Arteriosinusoidal vessels

- Aterioluminal vessels

Physiology

Myocardial Oxygen Uptake

At rest, the pO2 of the blood in the coronary sinus is fairly stable at around 2.4-2.7 kPa (equivalent to saturations of 25-40%).

This demonstrates a relatively high oxygen extraction when compared to the systemic circulation.

This means that there is limited capacity for the myocardium to increase oxygen extraction when its oxygen demand (through increased work) increases.

As such, the increased demand must be met by increased coronary blood flow.

The resting myocardial oxygen uptake is about 9ml per 100g.

At rest, the pO2 of the blood in the coronary sinus is fairly stable at around 2.4-2.7 kPa (equivalent to saturations of 25-40%).

This demonstrates a relatively high oxygen extraction when compared to the systemic circulation.

This means that there is limited capacity for the myocardium to increase oxygen extraction when its oxygen demand (through increased work) increases.

As such, the increased demand must be met by increased coronary blood flow.

The resting myocardial oxygen uptake is about 9ml per 100g.

Coronary Blood Flow

The blood flow in the epicardial vessels is similar to the rest of the circulation.

However, the vessels subsequently supplying the myocardium are affected by the significant pressure changes that occur because the myocardium is actively contracting.

This increased pressure acts to reduce the pressure gradient that is the primary driver of blood flow, and this reduces blood flow.

As such, blood flow to the subendocardial tissue can be significantly reduced during systole, when the intramyocardial pressure can notably increase.

Again, there is a discrepancy between the sides, as the left ventricle generates notably higher intramural pressure, due to its increased work demands.

The clinical relevance of all this is that it means that the majority of coronary blood flow (particularly to the high pressure left ventricle) occurs during diastole.

As such, tachycardia, which reduces the length of diastole (as well as increasing myocardial activity) can negatively impact on coronary blood flow in patients with IHD.

It is also the diastolic blood pressure that is important as the driving pressure, rather than the systolic.

A further cause of decreased pressure gradient, is if the intraventricular end diastolic pressure is notably elevated (such as scenarios of excessive preload).

The blood flow in the epicardial vessels is similar to the rest of the circulation.

However, the vessels subsequently supplying the myocardium are affected by the significant pressure changes that occur because the myocardium is actively contracting.

This increased pressure acts to reduce the pressure gradient that is the primary driver of blood flow, and this reduces blood flow.

As such, blood flow to the subendocardial tissue can be significantly reduced during systole, when the intramyocardial pressure can notably increase.

Again, there is a discrepancy between the sides, as the left ventricle generates notably higher intramural pressure, due to its increased work demands.

The clinical relevance of all this is that it means that the majority of coronary blood flow (particularly to the high pressure left ventricle) occurs during diastole.

As such, tachycardia, which reduces the length of diastole (as well as increasing myocardial activity) can negatively impact on coronary blood flow in patients with IHD.

It is also the diastolic blood pressure that is important as the driving pressure, rather than the systolic.

A further cause of decreased pressure gradient, is if the intraventricular end diastolic pressure is notably elevated (such as scenarios of excessive preload).

Autoregulation

As with many local vascular networks, the coronary blood flow has tight autoregulation.

It works in similar ways to other vascular autoregulation, to automatically preserve blood flow, despite changes in myocardial substrate demand, and changes in driving pressure (i.e. aortic blood pressure).

The mechanisms of autoregulation are discussed elsewhere, but likely includes a combination of feedback from:

There are some of the autoregulatory mechanisms that may have clinical implication.

The autonomic nervous system balances vasoconstriction (alpha receptors) and vasodilation (beta receptors, parasympathetic activity).

The net balance appears to be one of vasoconstriction, as the denervated heart will demonstrate a period of coronary vasodilation.

As with many local vascular networks, the coronary blood flow has tight autoregulation.

It works in similar ways to other vascular autoregulation, to automatically preserve blood flow, despite changes in myocardial substrate demand, and changes in driving pressure (i.e. aortic blood pressure).

The mechanisms of autoregulation are discussed elsewhere, but likely includes a combination of feedback from:

- byproducts of metabolism e.g. adenosine

- stretch and reflex contraction of the supplying blood vessels

- neural and hormonal feedback mechanisms e.g. autonomic nervous system

There are some of the autoregulatory mechanisms that may have clinical implication.

The autonomic nervous system balances vasoconstriction (alpha receptors) and vasodilation (beta receptors, parasympathetic activity).

The net balance appears to be one of vasoconstriction, as the denervated heart will demonstrate a period of coronary vasodilation.

Cardiac Work

The oxygen usage of the myocardium is to allow oxidative respiration and provide high amounts of ATP for performing work.

It is therefore also important to consider the concept of ‘work’ as this ties in closely with oxygen demand.

An important differentiation is whether the heart is performing pressure work or volume work.

This concept is because the work that the heart has to perform (and therefore the energy and oxygen it requires) is higher to generate pressure.

This has important clinical ramifications, as it shows the impact of afterload on the oxygen demand of the heart.

This can be clearly seen in normal physiology by the notably increased oxygen demand of the left ventricle compared to the right.

They both pump the same volume of blood, but the systemic vascular resistance and systemic blood pressure is much higher than the pulmonary equivalents.

The oxygen usage of the myocardium is to allow oxidative respiration and provide high amounts of ATP for performing work.

It is therefore also important to consider the concept of ‘work’ as this ties in closely with oxygen demand.

An important differentiation is whether the heart is performing pressure work or volume work.

This concept is because the work that the heart has to perform (and therefore the energy and oxygen it requires) is higher to generate pressure.

This has important clinical ramifications, as it shows the impact of afterload on the oxygen demand of the heart.

This can be clearly seen in normal physiology by the notably increased oxygen demand of the left ventricle compared to the right.

They both pump the same volume of blood, but the systemic vascular resistance and systemic blood pressure is much higher than the pulmonary equivalents.

Substrate Use

The heart is pretty versatile in its use of substrates for metabolism.

Usually these are in the form of:

Almost no metabolism occurs via anaerobic pathways (<1%) and indeed this can be detrimental and even harmful to the myocardium.

The heart is pretty versatile in its use of substrates for metabolism.

Usually these are in the form of:

- 35-40% - carbohydrates (equal proportions glucose and lactate)

- 60% - fats

Almost no metabolism occurs via anaerobic pathways (<1%) and indeed this can be detrimental and even harmful to the myocardium.

Links & References

- Klein, A. Ortmann, E. Coronary Circulation. E-Learning for Healthcare. 2012.

- Cardiovascular Physiology Overview. Life in the Fast Lane. Available at: https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/cardiovascular-physiology-overview/

- Des Jardins, T. Cardiopulmonary anatomy & physiology: Essentials for respiratory care (4th ed). 2002. Delmar Thompson Learning.

- Pinnel, J. et al. Cardiac Muscle Physiology. CEACCP. 2007. 7(3): 85-88.

- Moore, K. Dalley, A. Clinically orientated anatomy (5th ed). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006