Perfusion

Last updated 26th February 2019 - Tom Heaton

The next key factors of gas exchange is perfusion of the lungs.

There are some key differences from the systemic circulation which are important to understand.

There are some key differences from the systemic circulation which are important to understand.

Pressures

The pressures within the pulmonary artery are around 25/8 mmHg (mean 15 mmHg).

The left atrial pressure is only 5 mmHg, so there is a pressure gradient of around 10 mmHg (around 10 times less than the systemic circulation).

Of note, the musculature of the pulmonary vessels is much reduced in comparison to the systemic circulation, and this is one factor that contributes to the reduced resistance to blood flow.

There is not the notable pre-capillary drop in pressure, as in the systemic circulation, and the pressure in the pulmonary capillaries is probably halfway between the arterial and venous values.

This fits with the differing function of the pulmonary and systemic circulations.

The systemic circulation has to pump blood against potentially significant pressures (e.g. against gravity to an outstretched arm) and with significant variations in distribution at times.

The pulmonary circulation simply wants to pump blood to the top of the lungs, and in a fairly homogeneous, mostly unchanging manner.

The set up of the pulmonary circulation allows this to occur in the most efficient manner, as little pressure is required.

The left atrial pressure is only 5 mmHg, so there is a pressure gradient of around 10 mmHg (around 10 times less than the systemic circulation).

Of note, the musculature of the pulmonary vessels is much reduced in comparison to the systemic circulation, and this is one factor that contributes to the reduced resistance to blood flow.

There is not the notable pre-capillary drop in pressure, as in the systemic circulation, and the pressure in the pulmonary capillaries is probably halfway between the arterial and venous values.

This fits with the differing function of the pulmonary and systemic circulations.

The systemic circulation has to pump blood against potentially significant pressures (e.g. against gravity to an outstretched arm) and with significant variations in distribution at times.

The pulmonary circulation simply wants to pump blood to the top of the lungs, and in a fairly homogeneous, mostly unchanging manner.

The set up of the pulmonary circulation allows this to occur in the most efficient manner, as little pressure is required.

Pulmonary Vessels

How the blood vessels act in relation to these pressures is important, and some facets will now be discussed.

However, it is first important to highlight that the blood vessels are probably best split into 2 categories:

Alveolar vessels are vessels that surround the alveoli i.e. the capillaries.

These have very thin wall to minimise distance for gas diffusion, and so they are high sensitive to alveolar pressure.

The difference between the intravascular and alveolar pressure i.e. the transmural pressure, will have a significant impact on flow within the vessel (as is described in West zones below).

Extra alveolar vessels are the larger vessels (veins and arteries).

Although they don’t have massively muscular walls (as noted) they are less impacted on by the alveolar pressure.

They are actually being ‘stretched’ open to some extent by the effects of the elastic recoil of the lungs.

This effect is greater at larger lung volumes, and in regions of the lung where there is preferential expansion (the apices).

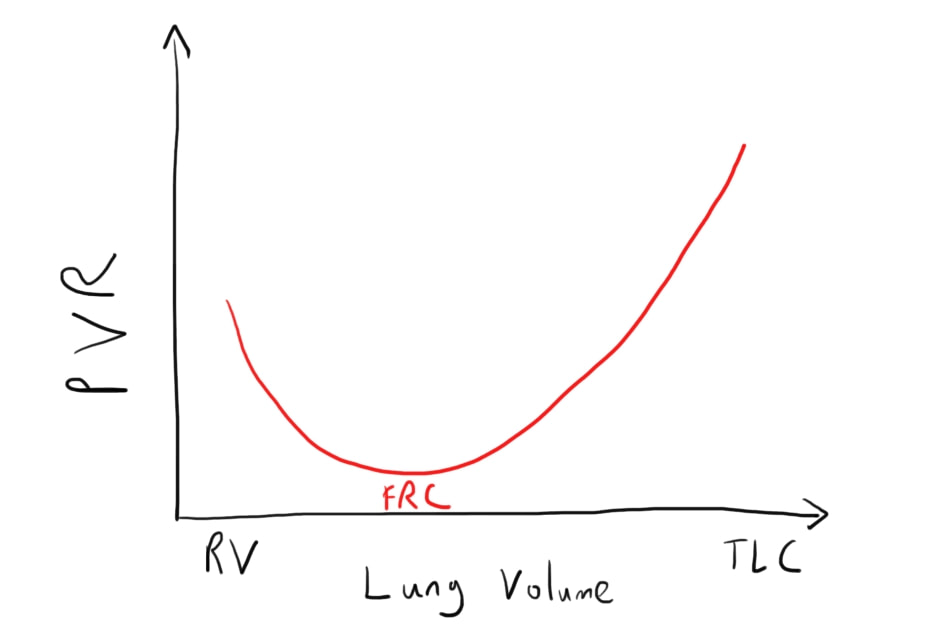

However, increasing lung volumes can also have a detrimental effect on pulmonary blood flow i.e. increase pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR).

This is mainly through the effect of this lung distension on the alveolar vessels.

Whilst the extra-alveolar vessels are stretched open, the alveolar vessels have only think= walls and so are stretched in a way that reduces their calibre.

At larger volumes, this increases the total pulmonary vascular resistance.

This give a U-shaped curve for PVR at different lung volumes, with the volume around the FRC being about the optimal.

However, it is first important to highlight that the blood vessels are probably best split into 2 categories:

- Alveolar

- Extra-alveolar

Alveolar vessels are vessels that surround the alveoli i.e. the capillaries.

These have very thin wall to minimise distance for gas diffusion, and so they are high sensitive to alveolar pressure.

The difference between the intravascular and alveolar pressure i.e. the transmural pressure, will have a significant impact on flow within the vessel (as is described in West zones below).

Extra alveolar vessels are the larger vessels (veins and arteries).

Although they don’t have massively muscular walls (as noted) they are less impacted on by the alveolar pressure.

They are actually being ‘stretched’ open to some extent by the effects of the elastic recoil of the lungs.

This effect is greater at larger lung volumes, and in regions of the lung where there is preferential expansion (the apices).

However, increasing lung volumes can also have a detrimental effect on pulmonary blood flow i.e. increase pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR).

This is mainly through the effect of this lung distension on the alveolar vessels.

Whilst the extra-alveolar vessels are stretched open, the alveolar vessels have only think= walls and so are stretched in a way that reduces their calibre.

At larger volumes, this increases the total pulmonary vascular resistance.

This give a U-shaped curve for PVR at different lung volumes, with the volume around the FRC being about the optimal.

Blood Flow

When blood flow increases e.g. the increased cardiac output during exercise, it could be seen that pressures might increase, as per the use of Ohm’s law in looking at the circulation (Q=P/R).

However, there are 2 main significant changes that occur in the lung blood flow in this situation:

Recruitment refers to the fact that many pulmonary vessels remain closed during normal conditions.

Small elevations in arterial pressure can allow these to open up, notably reducing the resistance of the pulmonary circulation even further.

Distension refers to the fact that some pulmonary vessels, which are open, are able to increase their diameter still further in the face of increased arterial pressure.

This increased calibre can occur because of the relative limited muscular nature of the vessels, allowing distension, and in the process allowing increased flow.

However, there are 2 main significant changes that occur in the lung blood flow in this situation:

- Recruitment

- Distension

Recruitment refers to the fact that many pulmonary vessels remain closed during normal conditions.

Small elevations in arterial pressure can allow these to open up, notably reducing the resistance of the pulmonary circulation even further.

Distension refers to the fact that some pulmonary vessels, which are open, are able to increase their diameter still further in the face of increased arterial pressure.

This increased calibre can occur because of the relative limited muscular nature of the vessels, allowing distension, and in the process allowing increased flow.

Regional Differences in Perfusion

The perfusion of the lungs is not homogenous across the different areas of the lung.

This is because of the reduced vascular control that is exercised by the body, as previously noted.

The result is that the hydrostatic pressure has much more of an impact that in the systemic circulation, and the subsequent effect that this has based on the alveolar and extra-alveolar vessel features described above.

The key factor to remember about hydrostatic pressure is that it will be lower (both arterial and venous) the further the level above the heart.

This creates identifiable zones within the lungs (often referred to as West zones):

This is because of the reduced vascular control that is exercised by the body, as previously noted.

The result is that the hydrostatic pressure has much more of an impact that in the systemic circulation, and the subsequent effect that this has based on the alveolar and extra-alveolar vessel features described above.

The key factor to remember about hydrostatic pressure is that it will be lower (both arterial and venous) the further the level above the heart.

This creates identifiable zones within the lungs (often referred to as West zones):

- This may occur at the top of the lungs, although not in health. Here the arterial pressure is not quite above alveolar pressure by the time it reaches this height. As such, blood flow through the lung unit does not occur. In health, this means that the arterial pressure at this height is 0 (as this is alveolar pressure) but the application of alveolar pressure (e.g. through IPPV) can require higher arterial pressure

- This will be mostly the higher zones of the lung in health. Here the arterial pressure is higher than alveolar pressure, but the venous pressure is lower. As such, the flow will be dependent on the arterial-alveolar pressure gradient (compared with the normal arterial-venous). Going down the lungs, the arterial pressure will steadily increase, and so more recruitment of pulmonary vessels will occur.

- This will be much of the normal lung.The arterial and venous pressures are both higher than alveolar pressure, so the flow is therefore dependent on the arterial-venous pressure gradient. Again the arterial pressure will increase down the lungs and so the gradient will increase - increased blood flow

- An interesting zone. This is related to the impact of lung volume on extra alveolar blood vessels. At low lung volume, the traction of the elastic lung on the blood vessels is reduced, extra-alveolar blood vessel calibre reduces and so does blood flow. This is more common at the bases of the lung initially, where the lung is less expanded.

Fick Principle

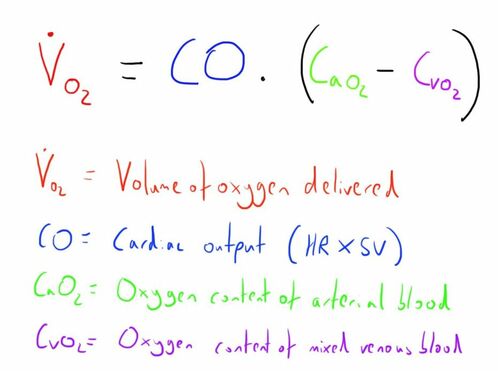

We may want to measure pulmonary blood flow.

This can be achieved using the Fick principle.

We can understand this as follows:

This can perhaps be better shown graphically.

This can be achieved using the Fick principle.

We can understand this as follows:

- Any oxygen that is taken up from the lungs must be taken up by the blood flow through the lungs

- If we can measure how much blood is taken up from the lungs we can work out the blood flow.

- We can start measure the volume of oxygen that is taken up from lungs by measuring the oxygen consumption at the mouth

- If we measure the concentration of oxygen in the blood before the lungs (mixed venous) and then after the lungs (arterial) we can work out what volume of blood this amount of oxygen must have been taken up into.

This can perhaps be better shown graphically.

The equation can be switched around to look at different components e.g. to look at tissue oxygen utilisation or cardiac output.

This is a nice quick review: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbHJh1r74PQ

This is a nice quick review: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbHJh1r74PQ

Control of Pulmonary Vascular Resistance

As noted, their is notably less control of the pulmonary vasculature than in the systemic circulation, but there still is some.

Probably the primary role of this is to direct blood towards the effective lung units, and away from ineffective or unventilated regions of lung.

This is to prevent shunting of blood and hypoxia.

This physiological response is primarily governed by the oxygen tension of the alveoli, and is termed hypoxic vasoconstriction, as at low oxygen tensions, pulmonary arterioles contract down.

This particularly starts to occur at partial pressures below 9 kPa (70 mmHg).

A number of other factors increase and decrease PVR:

Increase PVR:

Decrease PVR

Probably the primary role of this is to direct blood towards the effective lung units, and away from ineffective or unventilated regions of lung.

This is to prevent shunting of blood and hypoxia.

This physiological response is primarily governed by the oxygen tension of the alveoli, and is termed hypoxic vasoconstriction, as at low oxygen tensions, pulmonary arterioles contract down.

This particularly starts to occur at partial pressures below 9 kPa (70 mmHg).

A number of other factors increase and decrease PVR:

Increase PVR:

- Raised pCO2

- Low pH

- Sympathetic ANS - adrenaline/noradrenaline

- Thromboxane A2

- Angiotensin II

- Serotonin

- Histamine

Decrease PVR

- Low pCO2

- High pH

- Parasympathetic ANS - ACh

- Nitric oxide

- Prostacyclin

- Volatile anaesthetic agents

Lung Fluid Balance

This is an important physiological issue because of the proximity of the capillaries to the alveoli.

Starling’s forces are still at play in the lungs, as in the capillaries peripherally, although some of the values are less clear.

There is probably a small net external movement of fluid from the capillaries into the lung tissue (about 20ml/hr).

This then travels to the peribronchial region where there are lymphatics that return it to the systemic circulation.

It is these peribronchial tissue which become increasingly engorged as the first stages of pulmonary oedema.

Starling’s forces are still at play in the lungs, as in the capillaries peripherally, although some of the values are less clear.

There is probably a small net external movement of fluid from the capillaries into the lung tissue (about 20ml/hr).

This then travels to the peribronchial region where there are lymphatics that return it to the systemic circulation.

It is these peribronchial tissue which become increasingly engorged as the first stages of pulmonary oedema.

Links & References

- West. B. Respiratory physiology: the essentials (9th ed). 2012

- Cross, M. Plunkett, E. Physics, pharmacology and and physiology for anaesthetists: Key concepts for the FRCA. Cambridge University Press. 2010.

- Robertlouisherron. Fick principle overview. Youtube. 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbHJh1r74PQ